Analysing the Music of Thomas Adès

On 28 July 2021 Edward Venn will be presenting a paper, 'An Excursion through Haunted Libraries: The First Movement of Thomas Adès’s Concerto for Piano and Orchestra' as part of a panel session, 'Analysing the Music of Thomas Adès' that he convened for the Birmingham Music Analysis Conference (BrumMAC, 28-30 July 2021). This paper, along with contributions by fellow panelists James C. Donaldson and Richard Powell, will form the basis of a symposium (with an additional article by Arnold Whittall) to be published in TEMPO in autumn.

'An Excursion through Haunted Libraries' is part of a larger examination of the relationship between tonality and form in Adès's music (and in particular how this relationship is manifested in the operas), and draws also on research carried out as part of Thomas Adès Studies.

Abstract:

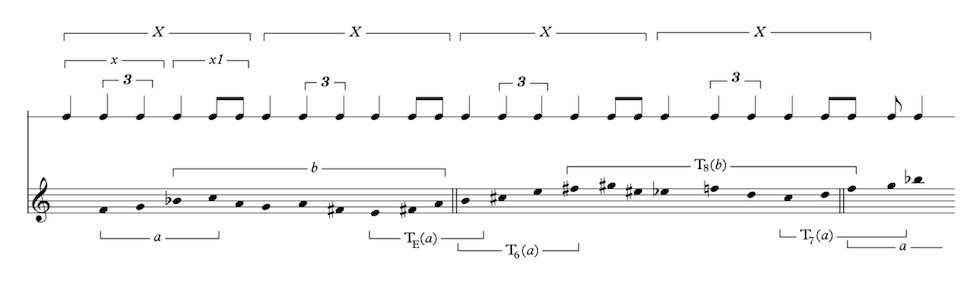

There is a striking similarity between the opening of Adès’s 2018 Concerto for Piano and Orchestra and Gershwin’s ‘I Got Rhythm’. Adès has since claimed ‘that wasn’t a quotation … But then all of our minds are kind of haunted libraries and so these things are there in some way’. Yet if Gershwin, and more intertextual echoes that might be heard, occur fleetingly on the musical surface, the Concerto’s form is haunted by a more specific ghost. Encapsulating something of a critical consensus, Andrew Mellor has asked ‘is this the last Romantic piano concerto? [… W]e are in the footsteps of Rachmaninov’. Such an impression is reinforced by Adès’s programme notes to the Concerto, which Alex Ross describes as ‘almost comically old-fashioned, inviting the audience to listen for first and second themes, development and recapitulation, and so on’. Nevertheless, Adès’s productive dialogue with the past on both the surface and formal levels is largely taken for granted, and left critically unscrutinised. In short, a more detailed excursion through the haunted libraries of Adès’s music is long overdue.

The first movement of Adès’s Concerto provides an excellent point of departure. Here, my intention is not to consider the critical workings of such recollections. Rather, by situating the movement against the background of the Romantic Piano Concerto (as described by recent Formenlehre scholars), I shall demonstrate how Adès’s music creates the conditions for its own 21st-century formal functions and syntactical organisation, building upon, but in no way beholden to, the past.